For most of our documented history in Western Traditional art, the act of painting outdoors was limited to preparatory sketches for mapping out compositions before they were perfected and idealized in studios, and for centuries, classical portraits and landscapes relied on the patient hand of skilled masters painting over many sessions. The French term “Plein Air”, coined in 1813, describes a method of painting outdoors in order to render an image from real life.

Realism – a movement to depict scenes of real life instead of curated subject matter – arose in the 19th Century all over Europe. For the first time in European history, artists throughout the continent were documenting real-life events in real time, telling their versions of the truth. Paintings of harsh working conditions arose, often with an undergird of political statements. Depicting the real world would lead to the rise of French Impressionism in the 1860s, which introduced a whirlwind of massive changes in the realm of painting, but perhaps the most notable was the speed at which an artist could produce a finished piece.

The Realists and Impressionists pioneered the concepts of Modernism – a radical art movement that would expand beyond and diminish the rigid expectations held by classical tradition for centuries prior. Modernism allowed for painters to embrace their medium. Instead of creating a painting to appear like a photograph, artists began to make paintings to look like paintings. Brushstrokes were visible, texture and color were no longer limited, and finished paintings could be produced in one session.

Over a short period of time, the artworld exploded with naturalist landscapes and “impressions” of parties, cityscapes, and city parks. Traveling painters were setting up their easels right in the middle of the action, finding inspiration in front of the canvas, and finishing their work in one session.

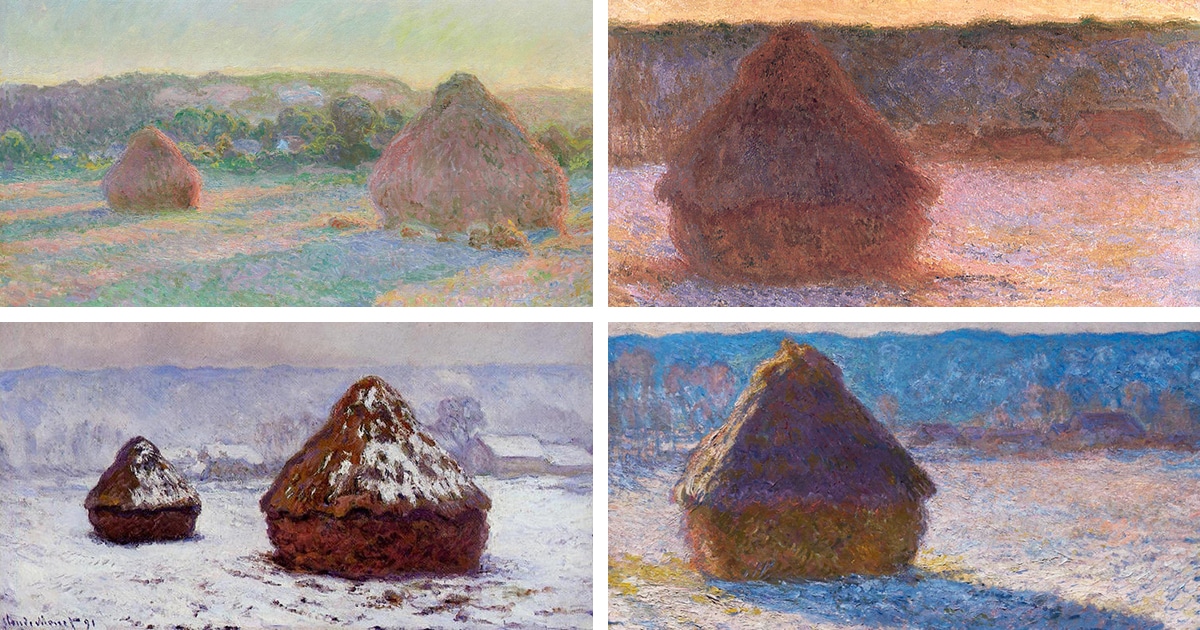

Claude Monet was arguably the most revered Impressionist. Monet’s iconic paintings of gardens and nature are treasured as masterpieces en plein air. He believed in painting in front of nature, so that he could render impressions in fleeting light. His dynamic and impressive haystack series features multiple paintings of the same field in different seasons and times of day. He painted the haystacks again and again, not necessarily for their appeal, but for the beauty of their evolution. This is a prime example of the power in painting quickly, capturing the singularity of a moment in the midst of change.

Altamira Fine Art represents Jivan Lee, the seasoned plein air painter with a similar philosophy. Native to Taos, NM, Jivan paints landscapes of his home terrain in the same locations repetitively over months, seasons, and years. “My all-season outdoor studio unrolls out of the back of my 4x4 pickup truck’s bed and shelters me just enough to paint in extremes of weather and season, but by design leaves me uncomfortably subject to their whims.” Jivan’s paintings are rhythmic, colorful, textural responses to the Western landscape in its many forms. The heart of his practice is this intensive outdoor painting process that embraces the body’s felt experience as a means for exploring time, change, and the complexities of how humans see and shape the environment. In in an interview with Southwest Contemporary magazine, Jivan Lee discussed the philosophy and rigor involved in his painting series of more than 360 images of Taos mountain: 10,000 Mountains or Monument. He stated, “It became about the slow, about the value of doing something again and again. Most of life is not the initial burst, but the moments in between… The mountain is never the same mountain, and we are never the same as we meet it day after day,”

In in an interview with Southwest Contemporary magazine, Jivan Lee discussed the philosophy and rigor involved in his painting series of more than 360 images of Taos mountain: 10,000 Mountains or Monument. He stated, “It became about the slow, about the value of doing something again and again. Most of life is not the initial burst, but the moments in between… The mountain is never the same mountain, and we are never the same as we meet it day after day,”

The discipline of plein air painting is something to be admired and revered. The process is inconvenient, messy, and physically taxing, but the challenge deepens our human relationship with the natural environment. Artists all over the world continue this tradition in a cohesive effort to translate our fleeting vision into a permanent picture, resulting in paintings that transcend our typical understanding.

Lydia Wilkes | July 25, 2024“For me, a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life – the light and the air which vary continually. For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere which gives subjects their true value.” – Claude Monet